Sandbox

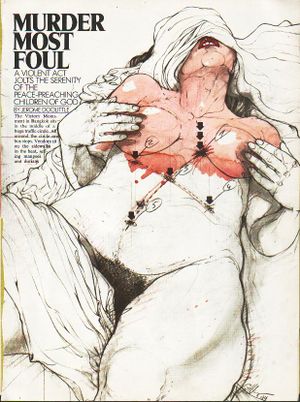

Murder Most Foul

A Violent Act Jolts the Serenity of the Peace-Preaching Children of God

Oui Magazine/February 1975

by Jerome Doolittle

The Victory Monument in Bangkok sits in the middle of a huge traffic circle. All around the circle are bus stops. Vendors sit on the sidewalks in the heat, selling mangoes and durians and mangosteens and little pieces of broiled chicken liver spitted on bamboo slivers. People are everywhere, practically all of them Buddhists. Three are not, though. They are:

- Little John, 20 a Thai student wearing a faded-blue T-shirt decorated with a giant Levi Strauss & Co. emblem

- Gang, a four-year-old Thai boy

- Shema, an 18-year-old American girl who is braless in accordance with the precepts of her religion, which is Christianity as interpreted and amended by David Brandt Berg, 55, aka Moses David.

The three are passing out Thai translations of a brief tract called "You Gotta Be a Baby." It reads, in part: Dear Lord, please forgive me for being bad and naughty and deserving a good spanking! Thank You so much for sending Jesus, Your son, to take my spanking for me.

They are distributing the tracts on behalf of a sect called the Children of God, and the distribution process is know as litnessing- witnessing by literature. For a time there, the Children of God in Bangkok had to cool it on the litnessing, but now the hullabaloo over the murder has pretty much died down and they are back at it again, as other Children of God are doing in 100 countries all over the earth. Praise God!

In Bangkok the Children of God work out of a former noodle shop in an alley behind a movie theater. The neighborhood is not fashionable and neither is the theater. One day not long ago, to give you an idea, it was playing a winner called The Crazy Boys at the Supermarket.

The steel folding shutters of the noodle shop were almost closed, leaving just enough of a gap for someone to squeeze through. Since the murder, no one at C.O.G. headquarters has been anxious to overexpose himself. Inside were two American males, caught in the tension zone between boyhood and manhood, complexions not quite cleared up yet. Around their necks, they wore chains from which hung small metal yokes, symbols of their servitude to God. On their faces, they wore smiles- the slightly awkward smiles offered by people told to smile for the camera.

OUI magazine? They were sorry, but they hadn't heard of it. It sounded interesting, though; the human form was beautiful, nothing to be ashamed of. (Or parts of it, at any rate. In the letters of Moses, it is written: "I don't see anything beautiful about these crotch shots of the women sticking their fannies right under your nose." And it is further written: "You'd rather see some beautifully draped cloth covering that uncomely part' and making her form even more attractive, than just plain corny-porny, ugly-wugly, nitty-gritty, smarty-smelly, hara-kiri crotches!")

Perhaps I would like to stop by a little later in the day, when Gibeah would be there. Gibeah speaks for us. What hotel was I in? The Trocadero, hadn't I said? What room number had I said? I hadn't said, but it was 421. (Why would they want to know the room number? Did they want to visit me? With what in mind? I was nervous because of the murder.)

When I went back, it turned out that the Children of God were nervous about my motives, too. Gibeah, the spokesman, was a 23-year-old dropout from California State Polytechnic. (Like all Children of God, he abandoned his worldly name for a Biblical one upon joining the sect.) He was dark-haired, medium-sized, slim, mild-mannered, carefully polite, worried. "You can understand how careful we have to be," he said. "I'm sorry, but how do we know you're who you say you are?" We went upstairs to the phone and Gibeah called the United Press International and the American Embassy, checking me out with friends of mine at both places. Downstairs again, we made arrangements for me to come back later in the week and spend a day with the colony. I was half a block away, heading for my hotel, when I heard Gibeah call out behind me. When he caught up, he said, "I'm sorry, and you're probably going to think we're all crazy, but look: We're convinced now that there is a Jerry Doolittle and that he's doing a legitimate magazine article, but how do we know that you're that Jerry Doolittle?" I said I would bring my passport next time and he said that would be fine.

At the time of my visit, the Bangkok colony consisted of ten brothers and sisters, all in their late teens or early 20s. One was a Dutch-Indonesian; the others were American. When I showed up, after my day spent studying their literature, the ten were seated in a circle waiting for me. Once they had made room for me in the circle, Gibeah, on guitar, began to lead the other in Children of God hymns- song after song, with hypnotic hand clapping- and at the end came the main song.

"This is sort of our theme song all over the world, isn't it, gang?" Gibeah asked.

"Yeah, yeah, amen," everybody murmured.

The song was called You Gotta Be a Baby to Go to Heaven, and they sang it in English, Persian, Indonesian, Spanish, Dutch, German, Japanese, Thai and French ("Redeviens un bebe pour aller au ciel") Finally, Gibeah said, "Do we all love Jerry?"

Everybody shouted "Yes!" but me, who knew him better and had reservations.

We danced around in a circle then and joined hands. "All who love the Lord raise their hands," Gibeah said, and we obeyed. Gibeah prayed. At the end of the prayer, he said, "The day we die is the day we start living. Right?"

"Right!" murmured all the Children of God.

To me, Gibeah said, "We don't have any stained-glass windows or collection plates. Just a lot of love, a lot of Don X Quixotes."

Various Children armed with tracts then went out to tilt at the Lord Buddha's 2,000,000 or so followers in the Bangkok area; others went on errands to the market or the post office. Two Thai students walked in wearing white shirts and shoes with chunky heels. "My friend would like to correspond ideas," one of them said. The friends smiled and said nothing. Thais smile when they are embarrassed. One of the Children, a girl, took the two boys over to a table, where she began to correspond ideas in a low voice. Gibeah sat with me at another of the homemade tables and talked. In no special order, here are some of the things he said:

"Horeb speaks the best Thai of all of us, but we're still limited to Thais who speak some measure of English. We're trying, though. We hired a Thai student to give us lessons every day."

We believe in counseling about our decisions. Of course, if you come right down to it, there has to be a decision maker." Was that he, then? Gibeah? "Let's just say I'm a spokesman."

"We pattern out lifestyle after the book of Acts: And all that believed were together, and had all things common; and sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.'"

"We're not interested in becoming a crash pad, because what we are is an army. The weapons of our warfare are not carnal. But there's nothing more revolutionary, we feel, than love."

"Last weekend, about 125 guests showed up for the sort of open house we have every Friday and Saturday." Were the rumors I had heard true, that communion sessions in the nude were sometimes held upstairs? "I've never seen that," Gibeah said. "I've never heard of such a thing."

Was the coffee-shop approach effective? Little John, an associate member who lived with his natural family, seemed to be the only Thai in regular attendance. Had they made other converts? "We've converted hundreds, but they don't necessarily become full-time members. The born-again experience is a conversion."

"A shepherd leads sheep; others try to drive them. It's the love we feel that's got to lead them to Jesus. Of course, we've made mistakes..." What mistakes? "Oh, at first, sometimes we might have gone a little too far with some of our training methods.." Such as compulsory memorization of endless verses, never leaving a new recruit alone, constant blaring of taped quotes from the Bible and the Mo letters and similar hard-sell tactics, which the sect's critics claim add up to brainwashing? Gibeah refuses to be drawn into the subject.

"A sample is better than a sermon." Gibeah and the others said this many times. It doesn't mean doing good works, because orphanages, school's and hospitals are not the Children's thing. It seems to mean displaying their way of life to as many other young people as possible. (The assumption- unadmitted, unspoken but hard to mistake- is that older people are hopelessly beyond redemption.)

Bangkok got its first sample of the C.O.G. way of life more than a year ago, when two advance men showed up in the Thai capital. For seven or eight months, they went about the city making contacts, lining up sympathizers and support, checking on immigration and visa policies, examining possible lodging-houses. Finally, everything was ready for the permanent colonists, who installed themselves unobtrusively in the former noodle shop. The colony's only sign of affluence (and it's a minor one in a country where wages are so low that textile workers recently went on strike for a pay hike to a dollar a day) is a maid who does the cooking and the cleaning. The Chinese woman who owns the small four-story building still lives there with her family in a room on the second floor. The Children of God rent the rest of the building, two of the men occupying the ground floor to guard against thieves.

For months, the Children issued forth from their alley day after day, flogging the Word in the streets. All was well, and regular reports on how many souls were being saved and that sort of thing were going up the line to the sect's distant and mysterious leader. Just your typical bunch of Jesus freaks, you might say, trying to make a go of it in a major Buddhist capital.

And then one day, a couple of young women showed up at the coffeehouse, curious about what was going on. They didn't say who they were, but one was Claudia Ross, an American reporter for the English-language Bangkok Post, and the other was her Irish roommate, Lillian Woods. The story that resulted from their visit filled most of the front page of the Post's Sunday magazine on March 24, 1974. "THEY CALL THEMSELVES CHILDREN OF GOD," went the headline, "BUT THEY PREACH HATE." The article began, "Sheltered by a camouflage of religious righteousness, the Children of God is really a parasitic cult of Bible-pounding automatons. Their theology teaches fanaticism, and their dogma preaches hate."

The rest of it was pretty much along the same lines.

With mournful, hurt expressions, the Children of God showed up in the city room the next day to ask Post managing editor Graeme Stanton for equal space. Stanton agreed, and the Children's rebuttal ran in the Friday, March 29, editions.

Earlier that morning, around three A.M., Claudia Ross was stabbed to death in her house.

Miss Ross was found laid out on the floor beside her rattan bed, a sheet drawn over her boday. Her hands were crossed on her chest. She had been killed by a deep stab wound in the heart, and four other knife wounds marked her chest and abdomen. These four cuts were hardly more than scratches and seemed intended to form a design, rather than to kill. The design made by all five wounds was a cross. The prints of two large sneakers were found inside the bedroom, under the window. They were reversed- the left where the right should have been and vice versa- just as Christ's feet, in some depictions of the Agony, are crossed. The window screen had been cut, as if to suggest that a burglar had gained entrance through it. But the cut had bent the little ends of the screen wire outward, not inward. The maid's brother-in-law, wakened by the victim's screams, got to his window in time to see a large, sturdily built man climbing over the garden fence. At just that point, the police found an electric typewriter that belonged in the house, but the typewriter disappeared shortly afterward while police and sight-seers were milling around outside the house where Miss Ross had been killed.

Police theories at various times were that Miss Ross had been killed in her bedroom, in the bathroom, by someone she knew, by a sneak thief, for political reasons, by a lone murderer who entered by the door, by two murderers who climbed through the window.

Unofficial theories were just as diverse and considerably more bizarre. Miss Ross, as it happened, admired Mao Tse-tung, hated United States policy in Asia, had a low opinion of America generally and particularly loathed the Central Intelligence Agency.

And the CIA has been particularly active in Thailand. Over the years, it had pumped millions and millions of dollars into the monumentally corrupt military junta that was overthrown in 1973 by student rebels. The students have not forgotten this. Let a public opponent of the CIA's stupid meddling die in an auto accident- as one did last June in north-eastern Thailand- and some will blame the agency. In August, a student leader was shot to death at a Bangkok bus stop. Again, some blamed the CIA.

Miss Ross not only was friendly with leaders of the student movement; she was also, friends say, at work on an article about agency involvement in Thailand at the time of her murder. Americans in Bangkok who share her high estimation of the CIA's malevolent efficiency speculate that the agency may have had her killed because her investigations were getting too close for comfort.

But those who know anything about the agency will recognize how absurd a notion this is; there is not enough creativity in the entire CIA for it to have conceived of so imaginative an assassination. Nor is there an American spook in Thailand bright enough to pull off a murder without leaving behind a photo of the wife and the kids, his embassy I.D. and his lifetime-membership card in the Knights of Columbus. Or so we may surmise from a recent piece of CIA childishness, in which an American agent sent the Thai prime minister a phony letter purporting to come from an insurgent leader. Probably nobody would have dreamed that it really came from the silly old CIA if the agent's return address hadn't appeared on the registration form filled out at the post office.

Not only is the CIA too unimaginative and too incompetent to have carried out the Ross murder; it was probably indifferent about whether she lived or died. The agency has been exposed by journalists much more expert than Miss Ross, all of whom lived to tell their tales.

Could the murder, then, have been the work of an outraged Thai patriot? Claudia Ross was outspoken, to use the kindest word possible. She was given to saying, in public gatherings, such things as,"Thailand will never make any progress till it gets rid of Buddhism and the monarchy." But even the grossest insensitivity hardly seems compelling as a murder motive. And besides, how many Thais would be solidly enough grounded in Christian symbolism to set the stage as it was set?

How many Thai policemen, for that matter, would recognize the sect for what it was? Or be able to figure out whether the Children of God were to be taken seriously as missionaries or lightly as young kooks? Or make sense out of the lifestyle of a left-wing, 27-year-old reporter born in Brooklyn? Cultural riddles were everywhere you turned. At one point, for example, the investigators were baffled by a notation they had found, in the dead woman's handwriting. They had looked the words up conscientiously enough, and each word seemed to have a plain dictionary meaning. But put together, they were nonsense. Finally, the detectives asked Miss Ross's roommate, Lillian Woods, whether the notation was in code.

The words were Dial-A-Dildo, and Miss Woods does not remember as her most comfortable quarter hour the time spent explaining to the Thai police that the two single women were talking one night about their impression that every attractive man in Bangkok was either queer or married, and they got to thinking about those Dial-A-Prayer things, and Dial-A-Joke, you know...Well, anyway, they were saying to each other- just kidding, you understand- wouldn't it be funny if they started this new service, you see, and called it, well..."

To the police, the Children of God must have seemed much less odd. Religious practitioners of any persuasion are automatically treated with respect in Thailand, and Christian missionaries have made considerable contributions to the country in the medical and educational fields. Religious intolerance is foreign to Buddhism, which has survived through the centuries by welcoming new faiths with a serene, untroubled smile, adopting from each whatever features seemed interesting. "Not only are these holy kids," says one longtime Bangkok resident, an American; "these are nice kids, too. A cop's kind of kids. They wash and they shave and they cut their hair and they wear clean clothes and smile and act real polite. The cops seem to have figured that any kids as nice as they couldn't possibly have murdered Claudia."

Not that the American himself really believes that the Children of God did it. "But you know," he says, "it's just that if you fill an empty head up with all that garbage, maybe once in a while the mixture will turn out to be explosive. Kill for Christ. After all, look at all that symbolism. Who else but some kind of nut..."

The world is full of nuts, though, many of them capable of reading the Bangkok Post's Sunday magazine and absorbing its contents sufficiently to frame a bunch of Jesus freaks. The truth is that no one has come forward with the slightest evidence of the Children of God's being implicated in the Ross killing. And yet the speculation continues, perhaps because all that is generally known of the sect by Bangkok residents comes from the hostile article written by miss Ross. Since the murder, there has been no news about the sect, and many Americans in Bangkok believe that the Children of God have left the country.

Actually, the Bangkok colony lay low after the murder- at some financial cost. Each colony aims to be self-sustaining, meeting expenses from money sent by parents or other supporters or from donations received while litnessing.

"But for a couple of months after the Ross death," Gibeah said, "we stayed pretty much off the streets. We were practically living with the cops for a while there. Our income dropped to almost nothing and we had to get help from our brothers and sisters in Australia. In a way, though, it was a good thing. It gave the cops a chance to see what we were really like."

Even now, the Bangkok colony, unlike many others, does not do what the Children of God call Holy Ghost samples- singing and dancing in the streets to draw a crowd. "We're not particularly trying to call attention to ourselves here," Gibeah said.

But hustling tracts quietly is OK, and all through the day, Mercy and Jamin and Jamin (another Jamin; there are only so many names in the Bible) and Zatthu and Morning Star and Ariel and Horeb and Maresha had been going in and out, armed for the Jesus Revolution with black shoulder bags crammed with literature, Bibles, notebooks, wallets, maps, passports, address books and coffee-shop invitations. Now Shema and Little John were just going out, along with Gang, and I was to go with them.

Gang, the four-year-old Thai boy, had been in the coffee shop each time I had.

Whose boy was he? I asked Gibeah.

"I could just say he's God's child, but to answer your question, he's the son of a friend of ours."

Why wasn't he home? I asked.

"His mother sometimes leaves him with us during the day."

Who was his mother?

"Just a friend of ours."

Hard to say just what Gang's role was, then. When the Children of God don't want to talk about something, they have a way of retreating from the subject like frightened squids, leaving behind them a large, dark cloud of vagueness.

We bought ice-cream cones for ourselves and for Gang and rode the bus to the big traffic circle around the Victory Monument, where the buses stop.

Shema went directly about her business, smiling, saying only a word or two as she worked the crowd, passing out her pamphlets.

Gang wandered through all the legs, passing out pamphlets, too. He didn't seem to think it was much fun. He had a tendency to look around him and forget the tracts.

Like Shema, Little John smiled, too; but, being Thai, he was able to say a few words of explanation to each person he litnessed.

Little John and Shema litnessed to young people exclusively while I watched. The Thais were polite and held onto the little pamphlet instead of tossing it directly to the ground, the way less civilized people do. New Yorkers, say. One student put the pamphlet, unread, inside a textbook; some put it in their pocket; a few read it.

It reads, " God is our great Father in heaven and we are His children on earth. We've all been naughty and deserve a spanking, don't we? But Jesus, our big brother, loved us and the Father so much that he knew the spanking would hurt us both, so he offered to take it for us!"

This might have played in Peoria, as the criminals in the White House used to say, and maybe it will in Thonburi or udon Thani, for all I know. But I keep thinking of a friend of mine who looked over a high bluff one day in northeastern Thailand. At the bottom, on the bank of the Mekong River, three Thai boys lay side by side, jerking off.

They were being naughty and they deserved a spanking, no doubt about it, and they certainly would have got one if their moms had been anything like David Brandt Berg's mom, the fundamentalist faith healer.

But one man's fish is another man's poison, as the fella says, and those three Thai boys didn't seem to know that they were being naughty. They stopped for a minute, surprised, when they saw my friend looking down at them. But then they just laughed and went right on wacking away.